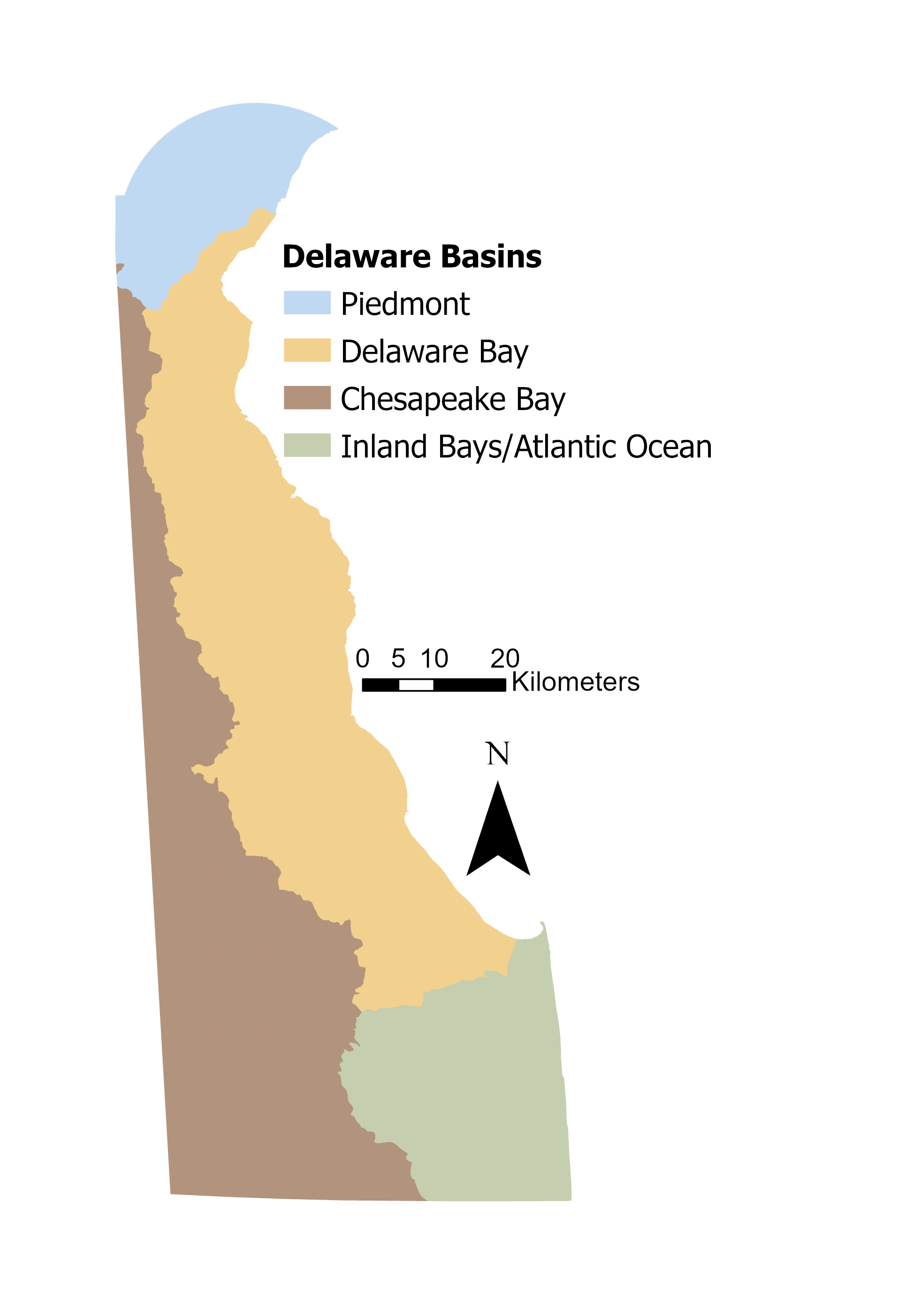

Delaware’s land area drains to three major watersheds, and contains four main drainage basins: the Piedmont, Delaware Bay, Chesapeake Bay, and Inland Bays/Atlantic Ocean basins.

Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control (DNREC) has been implementing a drainage basin approach to assess, manage, and protect Delaware’s natural resources.

This approach, known as Whole Basin Management, encourages the various programs from throughout DNREC to work in an integrated manner to assess different geographic areas of the state defined based on drainage patterns.

DNREC’s Watershed Assessment and Management Section oversees the health of the state’s water resources and takes actions to protect and improve water quality for aquatic life and human use. The Watershed Assessment and Management Section houses the Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program, which assesses the condition, or health, of wetlands and the functions and ecosystem services that wetlands provide. For more information, see Wetland Condition.

The Piedmont Basin and the Delaware Bay Basin are both part of the larger Delaware River Basin (a total of 642,560 acres in Delaware). The entire Delaware River Basin contains 13,539 square miles, draining parts of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, and Delaware, including the Delaware Bay, which lies roughly half in New Jersey and half in Delaware.

The Delaware Estuary (the Delaware Bay and tidal reach of the Delaware River and its tributaries) comprises three states (Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware), 13 counties, and 2 EPA regions. The Partnership for the Delaware Estuary (PDE), a nonprofit established in 1996, is one of 28 National Estuary Programs. PDE published its Technical Report for the Delaware Estuary and Basin in 2022 (PDE 2022).

The Piedmont Basin, considered separate from the Delaware Bay Basin because of its unique geology, empties into the Delaware River and is part of the Delaware Estuary. The Piedmont Basin contains the Brandywine Creek, Red Clay Creek, White Clay Creek, Christina River, Naamans Creek, and Shellpot Creek watersheds.

The Delaware Bay Basin is located in eastern New Castle, Kent, and Sussex counties. The basin is part of the Coastal Plain province, encompassing the following watersheds: Delaware River, Army Creek, Red Lion Creek, Dragon Run Creek, Chesapeake & Delaware Canal East, Appoquinimink River, Blackbird Creek, Delaware Bay, Smyrna River, Leipsic River, Little Creek, St. Jones River, Murderkill River, Mispillion River, Cedar Creek, and Broadkill River.

The Chesapeake Bay, the largest estuarine system in the contiguous United States, has a watershed of almost 64,000 square miles, one sixth of the eastern seaboard, and includes parts of Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, New York, Delaware and the District of Columbia. Delaware’s Chesapeake Bay drainage, spanning the western border of the state in all three counties, is about 1% of the land area of the entire Chesapeake Bay Watershed.

Despite its relatively small contribution to the overall area of the Chesapeake Bay Watershed, Delaware contains the headwaters of many of the rivers of the Chesapeake’s eastern shore. These ecologically important and sensitive areas provide important ecosystem services and host many species that are not otherwise found in Delaware.

In 2000, the State of Delaware entered into a Memorandum of Understanding with other jurisdictions in the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Chesapeake Bay Program to encourage participation in the restoration of the Chesapeake Bay by improving water quality in tributary rivers and creeks.

In 2014, representatives from each of the watershed’s six states signed the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement, a new accord to create a healthy Bay by accelerating restoration and aligning federal directives with state and local goals. This agreement guides the work of the Chesapeake Bay Program, and its science-based goals help partners track the health of the Chesapeake Bay. Recently, the Chesapeake Bay Program released a ‘Beyond 2025 Report’ to chart a path forward for the program.

The Nanticoke River is a major tributary of the Chesapeake Bay. Its watershed drains in Maryland and Delaware and is widely recognized for its unique biological communities.

Delaware’s three inland bays, Rehoboth Bay, Indian River Bay, and Little Assawoman Bay are separated from the Atlantic Ocean on the east by a narrow barrier dune system. Rehoboth Bay and Indian River Bay are tidally connected to the Atlantic Ocean by the Indian River Inlet. Little Assawoman Bay is connected by the Ocean City Inlet 10 miles to the south in Maryland. The inland bays are generally less than 7 feet deep, except in dredged channels, and are thus susceptible to pollution and eutrophication. The watershed of the Inland Bays includes 292 square miles of land that drains to 35 square miles of bays and tidal tributaries (Delaware Center for the Inland Bays 2012).

A new Delaware Inland Bays Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plan (CCMP), was released in 2021 (Delaware Center for the Inland Bays 2021). Only one major point sources of nutrient loading to the Bays remain of the 13-point sources initially identified. Nutrient management plans have been implemented for nearly all the farms in the Inland Bays drainage system, and thousands of acres of land have been placed under protection.

However, numerous challenges associated with development pressure and nutrient inputs to the watershed, and climate change remain. In 2023, the 2021 State of the Bays report was published (Walch et al. 2023), updating a previous 2016 report and outlining the condition of the bays using 39 environmental indicators. The Inland Bays are critical spawning areas for numerous species of estuarine fishes, as well as blue crabs and other aquatic life. The Bays are an important stopover and wintering ground for at least 25 species of waterfowl.

The Delaware Piedmont is composed of crystalline metamorphic and igneous rocks that are the remains of an ancient mountain building event that occurred many millions of years ago. These include a variety of rock types (predominately gneisses and amphibolites) that were formed by heating, deep in a subduction zone, mostly in the early part of the Paleozoic Era (400-500 million years ago), and then later uplifted. Also present are both extrusive igneous rocks (basalts) and intrusive igneous rocks (gabbros) that indicate the volcanic history of the region. This region is characterized by low, rolling hills and steeply incised stream valleys.

The Fall Zone, or Fall Line, is the dividing point between the Piedmont and Coastal Plain, and is characterized by areas of high stream gradient, exposed bedrock, waterfalls, and a mixture of metamorphic and sedimentary rock.

The Coastal Plain of Delaware is underlain by unconsolidated Quaternary sands, silts, and gravels that were laid down as beach, dune, barrier beach, saline marsh, terrace, and nearshore marine deposits. The Coastal Plain is a region of little topographic relief, with broad, slow-moving streams and extensive tidal estuaries.

Delaware has 80 described soil series and 195 discrete soil types (map units) (DE Natural Resources Conservation Service, NRCS).

The soils of the Piedmont are derived from the underlying gneiss and schist bedrock. They are older and tend to be more fertile than soils on the Coastal Plain. The soils in the valleys are rich and loamy, while the soils on steep slopes are often highly eroded and often rocky (Matthews and Lavoie 1970). Chrome soils from serpentinite occur locally and are low in calcium and high in magnesium, chromium, and nickel.

The soils of the Coastal Plain vary a great deal depending on geography and habitat. Sandy soils dominate throughout much of the region, but areas of clay or loamy textures are not uncommon. Soil drainage ranges from excessively drained in beach sands and on inland sand ridges, to very poorly drained in tidal marshes and swamps. Much of the Coastal Plain has been ditched to drain the land for agriculture (Ireland and Matthews 1974).

Extremely sandy soils of the coastal plain are of particular importance in structuring wildlife assemblages, because these dry, infertile soils support unique plant and animal communities. In particular, the Parsonsburg Sand, Quarternary-age remnants of an ancient sand dune (Denny et al. 1979; Denny and Owens 1979), supports dry pine-oak forests and woodland, home to several plants and animals that are absent from other areas of the state with more mesic, fertile soils.

Related Topics: action plan, conservation, draft, fish and wildlife, habitat, plan, species, wildlife