Outdoor Delaware is the award-winning online magazine of the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control. Articles and multimedia content are produced by the DNREC Office of Communications.

Delaware is home to more than 2,800 known animal species. Many are doing just fine or even thriving, but some are experiencing harder times. Whether because of climate change, invasive species, urban development, disease or other causes, a total of 90 kinds of animals that can be found in Delaware, from bats to moths to whales, are considered endangered by the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control.

These birds, mammals, amphibians, reptiles, fish, mollusks and insects on Delaware’s state endangered species list are at risk of vanishing from the First State. But nature lovers and government officials aren’t just sitting by.

All 90 aforementioned animals, plus about 600 more that aren’t yet state-endangered, are included in Delaware’s draft 2025-2035 Wildlife Action Plan as Species of Greatest Conservation Need, also known simply as SGCN. In total, there are 1,009 species on DNREC’s proposed list, including more than 300 plants — a new addition to this version of the Delaware Wildlife Action Plan.

DNREC, through its Division of Fish and Wildlife, creates a wildlife conservation blueprint every decade as per federal requirements. The resulting Delaware Wildlife Action Plan provides the outline for helping Delaware fulfill its responsibility to conserve our varied flora and fauna, as well as the natural habitats these plants and animals rely on. DNREC aims to ensure future generations can enjoy not only rare species but also ones that are currently common.

“The Earth is changing in many ways, and we need to make sure that we’re understanding how the wildlife that also occupy the Earth are changing along with it, whether it’s something we need to enhance or something we need to stop,” Sam Robinson, an environmental program manager in the Division of Fish and Wildlife, said.

Around a quarter of the known animal species in Delaware are considered SGCN, meaning they meet one of several different categories, such as being officially considered endangered by the United States Endangered Species Act, being listed as vulnerable by the nonprofit NatureServe or being judged by local experts to potentially be at risk in the near future.

The draft Wildlife Action Plan identifies and prioritizes 1,009 species in Delaware, placing them in several different tiers. The rarest species are prioritized at Tier 1, meaning they are most in need of conservation. Every species classified as endangered by DNREC falls into this category, including carpenter frogs, saltmarsh sparrows and tricolored bats, each of which gained this status last year.

Tier 2 species are of moderate conservation concern, while Tier 3 species are still relatively common but may be declining or are of local or regional importance or concern.

The plan includes about 150 species for which data is needed, known as assessment priority species, including the common raven. Additionally, there are seven extirpated species, such as the bobcat, which once existed in Delaware but have disappeared from the state’s landscape.

A few species have been removed as SGCN from the 2015-2025 version, either because they were found to have larger populations in the state than first thought or because conservation efforts proved successful — the best-case scenario for any creature or plant included in the plan. Other species may be doing better than a decade ago, such as the Delmarva fox squirrel, but are still included as SGCN because they remain threatened regionally.

Common stressors on species include loss of habitat due to climate change and development, as well as disease and the appearance or spreading of invasive species.

As well as the state-listed endangered species, 26 different animals found here are considered federally endangered, granting them protection from harm under the federal Endangered Species Act. Eighteen of those 26 overlap with the state list, leaving eight species that are officially endangered but are very infrequent visitors to Delaware.

“Our state endangered species list primarily focuses on those species that could be meaningfully protected or conserved in the state, and for which we have noticed substantial declines locally,” Robinson said. “For example, roseate terns breed north from New York to Eastern Canada, and in Florida, but not in Delaware and declines are not known to be associated with anything we are doing in Delaware. However, roseate terns could benefit from being an SGCN if we include it in our migratory species monitoring. Orcas, however, are very unlikely visitors to Delaware and wouldn’t benefit from much we could do locally.”

The number of bird species in the draft Wildlife Action Plan is down from the 2015-2025 iteration, which totaled 184 different species. Notably, the bald eagle is no longer listed, the result of a long recovery from hundreds of members of the species in the entire United States in the early 1960s to hundreds in the region today.

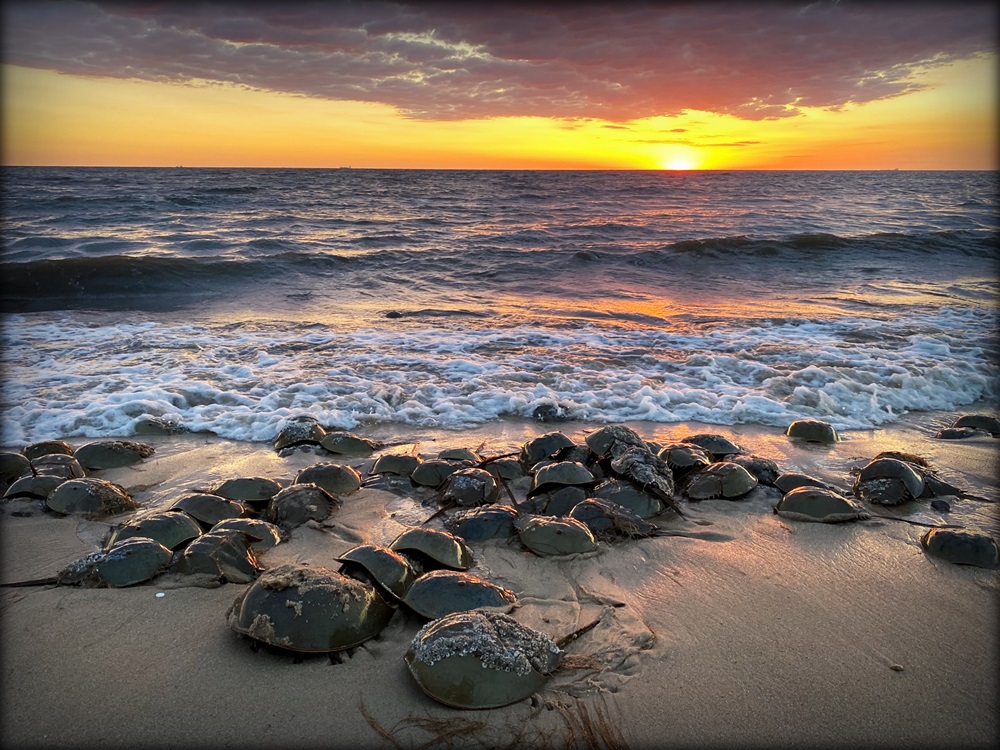

The draft plan does still include 164 species (roughly 40% of the known bird species in Delaware), including 53 designated as most in need of assistance. The list identifies a number of shorebirds, such as red knots and ruddy turnstones, many of which stop along the Delaware coast to feast on horseshoe crabs every spring as they migrate north. Others, such as piping plovers and American oystercatchers, rely on sandy beaches where they can lay eggs and raise young.

Other species listed as in need of conservation include the barn owl, peregrine falcon, golden eagle, American kestrel and mallard. New entries include the sandhill crane and common raven, both of which are listed as requiring more study.

Twenty-two bird species are considered endangered by the state. The federal government lists four birds that appear in Delaware as endangered, though three of those (the black rail, piping plover and red knot) are also listed by DNREC.

Habitat loss, predation, invasive species and disease are the main causes for the decline in bird populations in Delaware and worldwide. The Delaware Shorebird Project and Delaware Kestrel Partnership are among the many ways DNREC biologists are working to understand declines in avian species in Delaware, with these programs providing vital data to better manage and conserve these species with a goal of increasing their populations.

The number of fish included as SGCN totals 101, more than half of all fish species that can be found in Delaware waters, from the Atlantic to the Brandywine, although it is a slight decline from the 2015-2025 plan.

Among the fish species included here are the tiger shark, the nurse shark, the American eel, the Atlantic sturgeon, the northern puffer and the weakfish (which is the official state fish). Sadly, a handful of species, such as the blue ridge sculpin and the black-banded sunfish, may be extinct here.

Human activities affecting aquatic systems are the primary driver causing most of the listed species to appear in the plan. Habitat destruction, pollution, introduction of non-native species, disease, overharvesting and climate change all contribute to the health of different species’ populations.

Roughly 95% of all animal species on Earth are invertebrates. Delaware alone is home to at least 2,100 different invertebrate species, and while many of these are flourishing, some populations are struggling due to factors like the loss of critical habitats and use of some herbicides and insecticides.

Given the sheer number of invertebrate species around the globe, it’s perhaps no surprise this category (which consists of a number of taxa, including mollusks and insects) is the most well-represented in the draft Wildlife Action Plan, with 356 appearances. This section of the draft Wildlife Action Plan highlights iconic insects like the American bumblebee and the monarch butterfly as well as well-known ocean-dwellers like the blue crab and the channeled whelk (the state seashell).

Wildlife biologists are actively conducting surveys throughout Delaware to detect rare, localized populations, such as the Bethany Beach firefly with its distinctive double-green flash. The firefly is found in only a few locations along the Atlantic Ocean.

A rare ground-nesting bee species, Protandrena abdominalis, was discovered in Delaware for the first time in 2020, inhabiting unique sand habitats where it feeds only on the horsemint plant. Understanding the distribution of invertebrate species statewide helps biologists conserve those species and their habitats.

Delaware is home to around 60 different mammal species, 26 of which are listed on Delaware’s SGCN list. Those mostly can be classified as whales, bats or small land critters like shrews and weasels. Well-known species like the little brown bat and humpback whale show up here.

Notably, the grey fox, the state wildlife animal, appears as an SGCN, categorized as an assessment priority species, or one we still have much to learn about.

These high-priority mammals are often especially vulnerable to habitat loss. Small land mammals are also subject to unnatural predation by domestic pets and invasive species. Even whales, among the largest creatures to ever live, are suffering from climate change and ship traffic.

Several kinds of bat are considered SGCN. Species like the northern long-eared bat and little brown bat, both of which are state endangered species, have experienced population declines due to white-nose syndrome, a fungal disease that threatens bat species across the county. DNREC biologists are tracking bat populations and the effects of the disease in Delaware by performing bat colony counts and acoustic monitoring of bats.

However, big brown bats have been removed from the list because DNREC biologists have determined they have a sizable population in Delaware and are not as threatened by white-nose syndrome.

Other good news concerns Delmarva fox squirrels, which were common in the state until about a century ago. In 1967, they were listed as a federal endangered species by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service due to habitat loss and extensive timber harvesting. But, after conservation efforts in the region, the species was removed from the federal list in 2015, although it remains endangered here.

From 2020 to 2024, DNREC biologists transported 123 Delmarva fox squirrels from Dorchester County, Maryland, to Sussex County. So far, the project has been working, with documented reproduction at all three sites the squirrels were moved to.

Herptiles, or reptiles and amphibians, occupy 36 slots in the list, slightly down from 42 in the most recent Wildlife Action Plan. Still, they represent more than half of the known herp species in our state, as habitat destruction and fragmentation, disease, pollution and climate change have greatly impacted the frogs, snakes, salamanders and turtles (including land-based and ocean-based varieties) that call Delaware home.

Among the most well-known species listed here are the barking treefrog, tiger salamander, diamondback terrapin and copperhead. Notably, the loggerhead turtle, which was designated the state sea turtle in 2022, appears in the draft plan.

(If you’re keeping track, that’s four different state symbols that are listed as SGCN, though only the loggerhead and weakfish are Tier 1.)

As with other kinds of animals, herps are vulnerable to habitat loss, disease, pollution and predation. The diamondback terrapin, for instance, must deal with beach development and vehicle strikes during the breeding season as it ventures across roads to find nesting habitat. Fortunately, programs such as Operation Terrapin Rescue are working to help combat the effects of human impacts on survival and reproduction.

Delaware is home to more than 2,300 plant species, roughly 70% of which are native to the state. Although it’s easy to overlook the trees, grasses, shrubs and other flora that can be found here, whether along the salty coast or in urban northern New Castle County, plants are subject to many of the same stressors that plague wildlife.

Of the 333 plants included in the plan for the first time, 223 are Tier 2 members, meaning they have breeding populations in the state considered uncommon to rare, have broad distributions threatened by climate change and/or are species Delaware has significant responsibility for in the region.

Delaware has more than 1,600 native plant species, though around 40% of those are classified as rare. Among the Tier 1 species in the draft Wildlife Action Plan are Hirst Brothers’ panic grass and the mid-Atlantic beaksedge, both of which exist in only a few known locations across the country, including in Sussex.

Botanists with DNREC conduct statewide surveys to document the presence and distribution of rare plants and maintain records on plants and plant communities across the Delaware.

In addition to the plants and wildlife designated SGCN, the Delaware Wildlife Action Plan offers details about their habitats, key problems threatening them, potential solutions to these problems and more. It outlines the steps DNREC and its partners are taking to help keep today’s wildlife from becoming tomorrow’s memory.

The plan is meant to be actionable and relevant to all Delawareans. There are many steps people can take, from small actions like putting stickers on windows to prevent birds from flying into them unawares to preserving acres of land from development.

“We want to make sure that all of the wonder of wildlife is available for future generations and in perpetuity,” Robinson said.

The agency is not the owner or arbiter of the Delaware Wildlife Action Plan, merely leading the efforts to develop it, DNREC biologists emphasized.

To draft the 2025-2035 version, DNREC biologists used data and studies to update the previous list indicating the rarity of each species. Teams of taxa experts from within and without the department were convened to consider species for inclusion.

A draft of the final plan should be available for public comment sessions to be held in August, with the final publication set for the fall.

While the 2015-2025 Delaware Wildlife Action Plan consists of a series of PDFs uploaded to DNREC’s website, the intention is for the 2025-2035 to exist in a more interactive, user-friendly form somewhat analogous to a database.

The plan informs much of the work the Division of Fish and Wildlife will conduct over the coming years. Scientists from the division conduct surveys and detailed research projects to obtain scientific information about species and habitat distribution, abundance and population status as recommended in the plan.

Data offers important information to assist with identifying and tackling emerging issues such as diseases, invasive species or the long-term impacts from climate change.

Some steps, such as controlling the invasive wetland plant species phragmites, help minimize habitat stressors and improve key habitats for SGCN, while other efforts support regional partnerships.

DNREC works with many partners to help study and manage SGCN, including the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Delaware Department of Transportation, the Delaware Department of Agriculture, local governments, nonprofits and private landowners.

Among the many conservation projects DNREC is involved with are efforts to help boost the Delaware bog turtle population, which currently numbers around 20 adults. Turtles are tagged and eggs are taken to the Brandywine Zoo, where they are kept safe and warm until they are ready to hatch. After the young turtles have grown, they are released into the wild again.

Other efforts include developing and protecting a habitat for northern bobwhite quail at Cedar Swamp Wildlife Area and working with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to do the same for piping plovers at Prime Hook National Wildlife Refuge.

An important facet to this conservation work is acquiring land, specifically acreage that is home to potentially vulnerable species. In 2021, for instance, DNREC purchased 52 acres of tidal marsh as part of the Milford Neck Wildlife Area, which is very close to an important shorebird stopover site in the Delaware Bay. Conservation easements preserve land from development, enabling it to continue housing numerous species.

State wildlife areas, parks and estuarine reserves now collectively total more than 100,000 acres of state-owned land here.

“Everything’s interconnected. We’re all interconnected with the wildlife resources that are out there, the environment that they live in, the habitats that they use,” Division of Fish and Wildlife environmental program manager Anthony Gonzon said. “Conserving diversity allows us to have the ability to adapt and change over time. Without that diversity, we lose function in our systems. The roles that these critters play, whether it’s the tiniest insect or the largest bird, we can’t always accommodate for that.”

Related Topics: animals, conservation, endangered species, fish and wildlife, outdoor delaware, wildlife, wildlife action plan