Outdoor Delaware is the award-winning online magazine of the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control. Articles and multimedia content are produced by the DNREC Office of Communications.

Bats are frightening to many people. They’re often thought of as dirty, disease-ridden animals that want to suck our blood. None of these beliefs is true. Delaware’s bats are really quite small, have good personal hygiene, are timid and none of them suck blood. Our largest bat, the hoary bat, only weighs up to 1.5 ounces – the weight of about 50 paper clips.

Bats are far more beneficial than harmful. While we’re sleeping, bats protect us by eating insects that destroy our crops and spread diseases to humans.

Bats are often misunderstood. For starters, they’re not flying mice. Humans have a lot in common with bats. We’re both mammals who give birth to live young and feed them milk. Newborn bats, called pups, are dependent on their mothers and are limited in the number of young they can have per year. Most bat species have just one pup per year and don’t reproduce at all some years. We are also both long-lived. Several bat species live more than 30 years.

Bats don’t get stuck in your hair. In fact, bats are skilled at avoiding obstacles like us since they are able to echolocate — similar to radar — to explore their surroundings and to hunt. They are so precise, they can echolocate around a piano string and zoom in on tiny insects with ease.

Sometimes it might seem like bats are after you. But if they happen to zoom near, know they are looking for food, not you. As anyone that spends time outside in Delaware in the summer is aware, insects will buzz around us looking for a blood meal. Bats sometimes swoop close to humans to cash in on the insects we attract.

When they pass close to us indoors, it’s because they have limited room to fly and must swoop to stay airborne. They do NOT want to be there and are trying to find their way out. In addition to their echolocation skills, they can see quite well; about as well as most mammals – so the old “blind as a bat” saying is just wrong.

Bat are not out to get us. Most bat bites happen when people get too close to them. If you don’t touch a bat, it won’t bite you. The best thing to do is to leave them alone.

Help! There’s a Bat in My House!

What Do I Do?

There are things you can do when bats are found in homes, attics and barns, or other man-made structures. Learn More.

Bats are insect-eating machines, and they help control disease by eating insects — including pesky mosquitos that transmit diseases to us, like West Nile virus, malaria and yellow fever. Bats also eat moths and other agricultural insect pests. They are prey species for other animals. And, their poop, called guano, enriches the soil as a highly effective fertilizer containing key nutrients essential for plant growth. Bats are also good at fighting viruses. Scientists are studying this fact, which may lead to medical breakthroughs to protect us from some viruses.

Most of Delaware’s bats mainly hang out in woodlands and are seen looking for food over agricultural fields, ponds and creeks. Some bats will take up residence in attics, barns, garages, shutters and other human structures to raise their young.

We don’t have the typical hibernation locations, like caves or mines, but bats do hibernate in cave-like structures including those found at Fort Delaware and Fort DuPont state parks. Some overwinter in woodlands, wood piles and other structures. Others migrate to warmer climates.

Nine species of bats are found in Delaware. The most common species are the big brown bat and the red bat. Our rarest species include the eastern small-footed bat and three bats on our state endangered species list: the little brown bat, the tricolored bat and the northern long-eared bat. The tricolored bat is also proposed to be listed as endangered by the federal government, while the northern long-eared bat already is.

Sadly, all our known little brown bat colonies have been gone since the devastating fungal disease White-nose syndrome (WNS) was detected in Delaware.

White-nose syndrome is decimating bat populations throughout much of North America. Although not as prevalent in Delaware due to our lack of hibernation sites, it has wreaked havoc on our bat populations, especially our northern long-eared, little brown and tricolored bats.

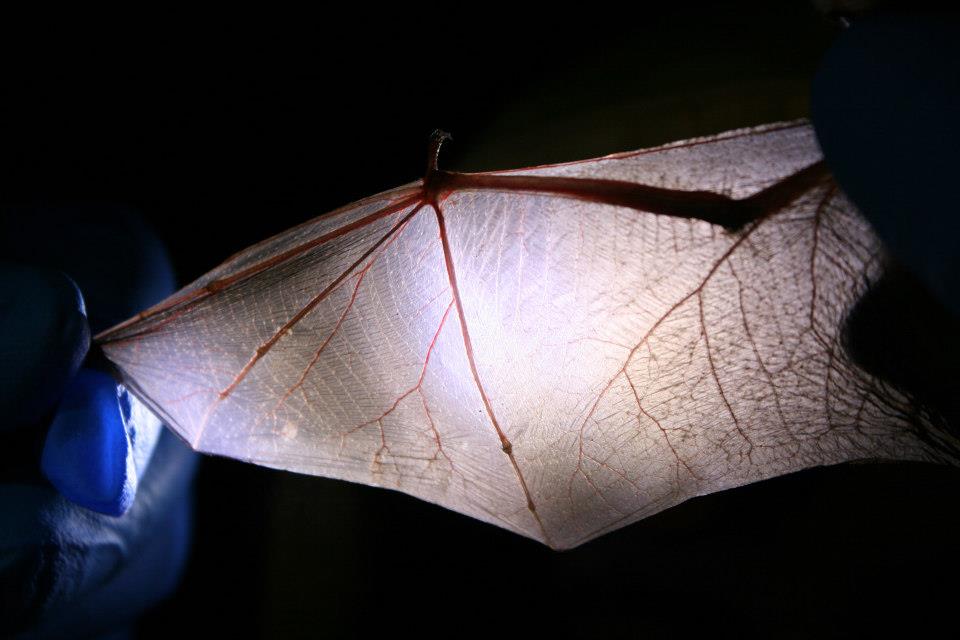

The disease affects hibernating bats in the winter when their immune systems are suppressed and many of their biological functions are slowed for energy conservation. The hallmark of WNS is the visible white fungal growth on a bat’s wings, forearms and muzzle. But after WNS has been at a site for a while, the fungus may not even be visible on the bat.

Some other threats to Delaware’s bats include habitat loss due to removal of forests, disturbance during hibernation and the maternity season, climate change, and human persecution driven by fear and misinformation.

The Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control works to prevent the spread of WNS to areas not already affected and to control it at Fort Delaware, where bats gather. DNREC is also working diligently to document locations of our rare species so scientists can help protect them and manage habitat for their benefit.

The Department has several long-term projects to monitor populations, including acoustic surveys (recording bat calls to determine which species are present), maternity colony counts and maternity colony health assessments. DNREC works with the public as well as commercial wildlife control companies to prevent human/bat conflicts and coordinate with other state and federal agencies.

Anyone can participate in some of these projects as Bat Spotters. Help is especially needed to find summer colonies.

The most important thing to remember about bats is that we’re a far bigger danger to them than they are to us. While all bats can carry the rabies virus, it’s estimated that only about 1% have it. You cannot get rabies from a bat flying near you or simply being present inside your house. You must make contact directly with bats to get the virus from them. The best thing to do is to not touch them.