Outdoor Delaware is the award-winning online magazine of the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control. Articles and multimedia content are produced by the DNREC Office of Communications.

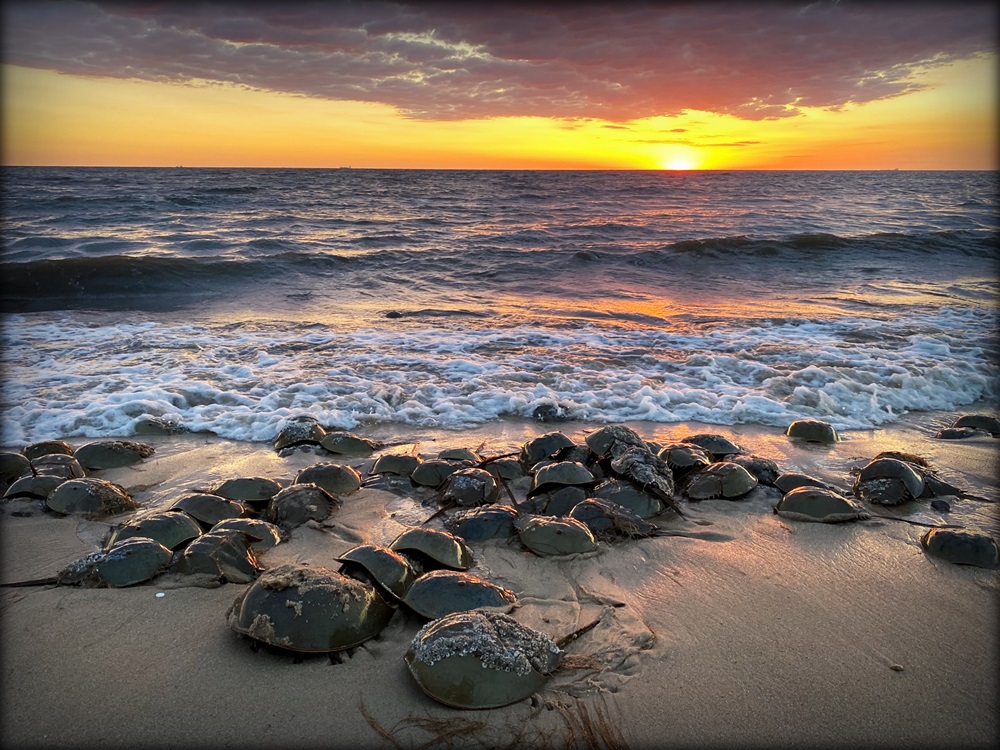

Every spring, millions of living fossils make their way to the beaches along the Delaware Bay, continuing a cycle that’s been underway for thousands of years. Creepy-crawlies more than a foot long clad in carapaces and trailing a tail-like spike emerge from the waves to gather along the shoreline en masse. They’re hoping to find a mate and in doing so help perpetuate their species, which has existed with relatively little change for hundreds of millions of years.

These creatures may seem to resemble something from science fiction, but they’re actually among Delaware’s most iconic wildlife. And, unlike just about every other species that can be found here, they’re practically straight out of the Triassic period.

These are horseshoe crabs, and the body of water dividing Delaware from New Jersey is home to their largest spawning grounds in the world. And don’t worry — despite a strange appearance, horseshoe crabs are harmless. In fact, their existence is beneficial to humanity.

Contrary to what their name implies, horseshoe crabs are not crustaceans. Rather, they are more closely related to spiders than the ghost crabs you see at the beach or the blue crabs you feast on. Globally, they can be found along the coasts in Southeast and East Asia, as well as the Gulf of Mexico. But it’s the North American Atlantic coast where they are most common.

Like clockwork, horseshoe crabs begin showing up along coastal Delaware beaches around the end of April, peaking at night with high tide during a full moon.

Though only around 800 square miles, the Delaware Bay is internationally famous for hosting horseshoe crabs, with some nature enthusiasts coming here from other continents just to witness the annual mating and egg-laying process.

“It might be a lesser beach, but any beach in the Delaware Bay area probably has more spawning than most beaches along the entire Atlantic coast,” said Jordy Zimmerman, a fisheries biologist in the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control’s Division of Fish and Wildlife.

At least part of the Delaware Bay’s popularity can be attributed to its bathymetry, or seabed topography. Unlike most places around the world, the Atlantic coast of the United States has numerous sandy beaches and estuaries separating salt water from wetlands. These beaches are relatively protected from wind and waves and free of hard structures that speed up erosion, and the tiny grains of sand found on the beaches are the right size for horseshoe crabs.

The bay’s salinity and tidal conditions also help make it a suitable nursery for young horseshoe crabs, which will spend about a decade living on the seafloor before they’re ready to mate. Over that time, the lucky ones will grow from roughly a centimeter to up to 2 feet long, molting about 16 times in the process.

All these factors contribute to making Delaware’s beaches a prime gathering place — Earth’s hottest horseshoe crab singles bar, if you will.

Such is Delaware’s prominence in the horseshoe crab lifecycle that the species was designated the state’s official marine animal in 2002.

Though a single egg is smaller than a grain of rice, one horseshoe crab can lay up to 100,000 eggs. Most of these eggs will never hatch but will instead be consumed by predators, helping fuel the circle of life.

Come springtime, hundreds of thousands of migrating shorebirds like red knots, ruddy turnstones and sanderlings make their way to the Arctic, with some traveling from as far as the southern tip of South America in hopes of mating. These birds use the Delaware Bay as a stopover where they can rest and gorge themselves on eggs, providing the energy needed to continue a journey that can stretch to 9,000 miles one way.

Without a healthy horseshoe crab population and the countless eggs female crabs lay every year, many shorebirds would face a decreased probability of nesting success.

What’s more, both horseshoe crabs and their eggs help feed species like loggerhead sea turtles and fish. Horseshoe crabs also contribute to the ecosystem by keeping populations of invertebrates like clams, mussels and worms in check and shifting sediments around the seafloor as they traverse the underwater terrain. Their shells can even serve as transports for creatures like sand worms and oysters that anchor themselves to the hard carapace.

Horseshoe crabs are an important part of the Delaware Bay ecosystem. And, like around 2,800 other animal species, they fall under DNREC’s purview.

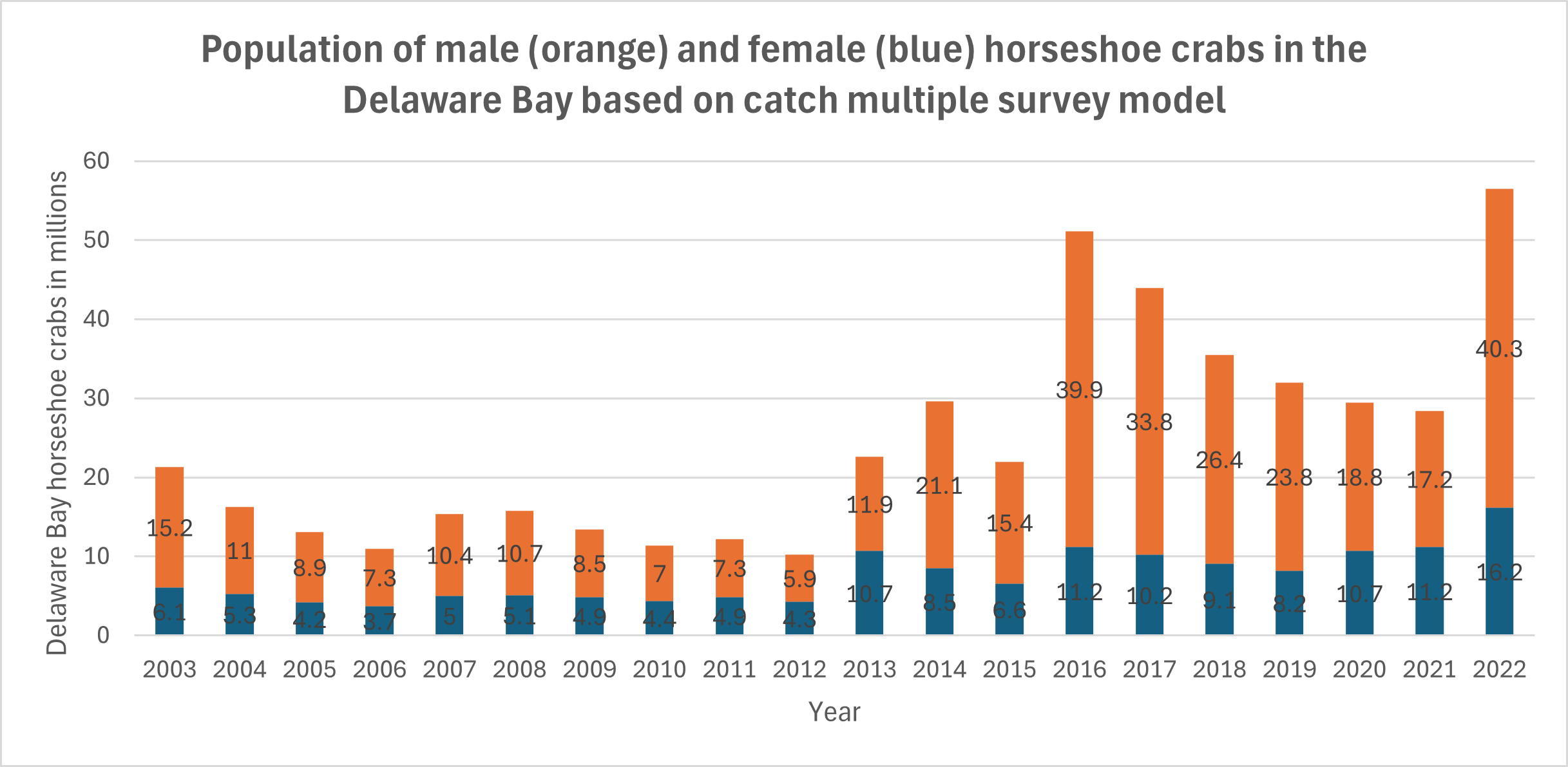

Today, the population of horseshoe crabs in the bay numbers in the tens of millions — a drastic increase compared to the turn of the millennium.

That upward jump is the result of a comprehensive effort to safeguard this key species, and it serves as a sign that limitations put in place to protect the humble horseshoe crab are working.

The harvesting of the species from the Delaware Bay goes back centuries, with Native Americans observed using dead horseshoe crabs as fertilizer in early Colonial days. In fact, according to a paper published by DNREC scientists, America’s indigenous inhabitants may have taught European settlers how helpful the crabs can be to stimulate crop growth.

By the mid-1800s, well over 1 million horseshoe crabs were being harvested annually from the Delaware Bay to be ground up and turned into fertilizer or fed to livestock, according to the DNREC paper.

But not all was well, and eventually, a clear decline in the population became visible. By the mid-20th century, the annual harvest was measured not in the millions but in the tens of thousands.

Though artificial fertilizers had eliminated one use for horseshoe crabs by then, other niches would soon pop up.

In the 1960s, scientists discovered an unusual property of horseshoe crab blood: it contains limulus amebocyte lysate, or LAL, which clots in the presence of pathogens. This trait makes the species’ blood extremely useful for detecting bacteria and toxins in people, drugs and intravenous devices and created a new demand for horseshoe crabs.

“Any pharmaceutical, any injection, any prosthetic, anything else that goes into a human’s body has been most likely tested by LAL,” Zimmerman said.

Horseshoe crab blood can be obtained without killing the crab, and crabs are required to be released to the water they were collected from after being bled. However, not all survive the process, with the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission, or ASMFC, estimating a mortality rate of around 15% after bleeding.

Delaware has never issued a scientific collection permit, which is required by state law for anyone hoping to collect crabs for biopharmaceutical purposes. In fact, DNREC has only had a few inquiries over the years, according to Zimmerman, who also noted any plan to bleed horseshoe crabs would need approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration as well.

Horseshoe crab usage for bait also picked up sharply in the 1990s, primarily for American eel and whelk pot fisheries. According to DNREC data, harvesting increased several times over from the early 1990s to the end of the decade, leading to roughly half a million crabs being taken from the Delaware Bay in 1997. Along the entire East Coast, about 2.8 million horseshoe crabs were harvested in 1998.

As a result, 1998 saw the first comprehensive multistate horseshoe crab management plan, developed by the 15 coastal states that form the ASMFC in response to the increase in harvesting and related concerns about the species’ long-term outcome.

“Concern over increased exploitation of horseshoe crabs, particularly in the mid-Atlantic States, has been expressed by state and federal fishery resource agencies, conservation organizations, and fisheries interests. Horseshoe crabs are important to migrating shorebirds and federally listed sea turtles as sources of food, and are critical to biomedical research and pharmaceutical testing. Because horseshoe crabs are slow to mature and easily harvested with minimal financial investments, populations are sensitive to harvest pressure,” states the commission’s 1998 horseshoe crab management plan.

Key to that plan was placing reasonable limits that would protect the population while still allowing commercial collection for bait and medicinal purposes.

Although Delaware already had restrictions on harvesting horseshoe crabs, such as requiring a permit, a more thorough solution was needed. The members of the commission worked together to develop regulations, and in 2000, the commission put forth limits for individual states while also recommending the federal government create prohibitions around harvesting horseshoe crabs in federal waters.

Check Out Some Horseshoe Crab Art

We asked Delawareans to send us their horseshoe crab art and we weren’t disappointed. Check out some of the stunning images submitted by readers.

In the first years of the restriction, Delaware was limited to 361,801 horseshoe crabs harvested (75% of the average from 1995 to 1997). Once that quota was reached, all harvesting would have to cease for the remainder of the year.

In the next few years, the quota would be lowered further, in part due to concern about the impact of overharvesting on shorebirds.

In 2013, the ASMFC adopted a new framework known as the Adaptive Resource Management model. Developed in part by DNREC scientists, the model utilizes horseshoe crab and red knot population surveys and estimates to recommend a harvest limit that considers both the commercial demand for horseshoe crabs and the ecological role they play in the Delaware Bay.

The model provides several potential options based on population dynamics, including a total harvest ban, allowing a limited number of males and no females to be harvested, and allowing members of both sexes to be harvested (albeit with the female quota still being lower than the male one). As per the recommendations, the commission has prohibited harvesting of female horseshoe crabs since 2013.

In this regard, Delaware is ahead of the curve: The First State has banned harvesting of female horseshoe crabs to help the species’ population grow every year since 2007.

In 2022, the framework used to set the quota was updated, and as a result of increasing female horseshoe crab abundance, the model showed a limited number of females could possibly be harvested. Although females are typically more valuable as bait because they are larger and emit certain pheromones that attract other sea life, concern from various stakeholders prompted the commission to disallow any female harvest while it conducted further research.

“The results of the survey confirmed that the various stakeholder groups hold divergent values and perspectives related to horseshoe crab management,” states the commission’s 2025 report. “Commercial industry participants indicated they still value the harvest of female horseshoe crabs, though it has not been permitted in the Delaware Bay region since 2012. Environmental researchers and advocates tended to value the protection of female horseshoe crabs and the ecological role of horseshoe crabs as a food source for shorebirds over the fishery.”

For 2025, the horseshoe crab cap for Delaware is 173,014, an increase of about 7% from the year before. In other words, once 173,014 horseshoe crabs (all of which must be male) have been taken from the water, Delaware harvesting operations must cease for the year.

The ASMFC adopted the most recent update to the Horseshoe Crab Fishery Management Plan in May, which allows setting annual male-only harvest quotas for the next three years.

As a regulator, DNREC is responsible for enforcing these restrictions, something made a bit easier by Delaware’s small size. Harvesters are required to call in their catch every day through an interactive voice response system, a responsibility not mandated of most fisheries, and DNREC has developed relationships with many harvesters and buyers, enabling the Department to stay on top of the horseshoe crab trade. Biologists constantly monitor how close to the quota we are, and enforcement checks take place on beaches where horseshoe crabs spawn to ensure compliance.

The state’s quota is conservative, with officials acting out of an abundance of caution to preserve the species while still supporting commercial fisheries.

“A well-managed fishery supports our watermen while ensuring there are plentiful female horseshoe crabs to provide eggs for migratory shorebirds,” Zimmerman said.

Additionally, legal harvesting doesn’t begin until June 8, after shorebird migration is finished for the season. If the quota still has not been met by August, horseshoe crabs can be harvested via dredging.

In 2024, the state only filled about half its quota, largely due to decreased demand for the crabs as bait for whelk.

As of mid-September, Delaware’s 2025 quota was 64% full.

For 2025, 23 licenses for harvesting by hand and five for dredging were available. License-holders have no annual limit on the number of horseshoe crabs they can take as long as the state quota has not been met, but no more than 3,000 crabs can be harvested per day by any licensee.

Violating any laws and regulations around horseshoe crabs is a misdemeanor subject to a fine of up to $1,000 and/or a jail sentence of up to 30 days, though penalties can double for prior offenses.

While New Jersey has had a moratorium on harvesting horseshoe crabs for bait since 2008, the state still allows biomedical collection, including females. Maryland also allows females to be collected and bled.

DNREC’s experts believe the balanced management approach has been a success, and they can point to data to back it up, chiefly the fact that Delaware has seen a steady increase in its horseshoe crab population in recent years.

A 2024 study from the ASMFC describes the Delaware’s Bay horseshoe crab population as good, with all five surveys conducted that year concluding the species’ population in the bay has increased since 1998. In fact, the population in the bay has grown more than threefold over the past decade and can be considered to have recovered from the lows reached about a quarter-century ago, Zimmerman noted.

According to a catch multiple survey analysis, there were approximately 56 million adult horseshoe crabs in the Delaware Bay in 2022, about 71% of which were male.

The current population, evidence suggests, is sustainable. The limits now in place through the ASMFC are working.

The population of red knots, the species that most heavily depends on horseshoe crab eggs, saw a steep decline around the turn of the millennium, largely as a result of overharvesting of horseshoe crabs, associated migration mortalities and reduced breeding success. Since 2011, the population in the Delaware Bay has remained stable, a sign the safeguards used by the commission, such as the model tying the allowable harvest to the red knot population, are having a positive impact.

Though the red knot population is not recovering at the rate biologists had hoped, there are many factors beyond the availability of horseshoe crab eggs, according to DNREC.

“This population’s annual cycle is complex and spans an enormous geographic area, with food availability during the Delaware Bay stopover being just one of the many critical drivers influencing survival and reproduction,” said Kat Christie, a coastal waterbird biologist in the Division of Fish and Wildlife.

While red knots have almost entirely abandoned the Delaware coast of the bay in favor of the New Jersey side, other species like ruddy turnstones and sanderlings show no such preference, Christie said. Theories behind this include the water temperature and spawning timing differences noted for horseshoe crabs on the shallower New Jersey coast, which has a wealth of protected beaches and marsh habitat that may better suit the birds’ needs.

“One thing is clear though: The availability of horseshoe crab eggs is the most foundational component of Delaware’s critical role in the ecological phenomenon of long-distance shorebird migration,” Christie said. “Continued research-based management of horseshoe crab fisheries and shorebird populations is essential for keeping this balance and doing our part to protect the global shorebird species entrusted to us by our lucky placement along their migratory route.”

Horseshoe crabs are a fascinating species. They’ve barely changed over hundreds of millions of years. They have important uses in the biopharmaceutical field and as bait. And, of course, they’re very unusual-looking and can only be found in a small portion of the country.

For some Delaware natives or long-time residents, seeing the crabs spawn every year is a rite of spring. Millions come ashore throughout May and June, crawling out of the depths of the Delaware Bay in hopes of mating with another member of their species.

So where exactly can you see these critters? DNREC recommends checking out some spots along the coast of Kent and northern Sussex counties. Slaughter Beach, Kitts Hummock and Pickering Beach all should offer ample opportunity to view horseshoe crabs. The DuPont Nature Center at Mispillion Harbor deserves special mention too.

DNREC also provides education workshops like Green Eggs and Sand, which has content for both teenagers and adults. And, people can sign up to be citizen scientists by helping survey the horseshoe crab spawning population in the spring. Just be sure to participate in the training first.

If you go to see horseshoe crabs, know that you should leave them alone except to flip ones stuck on their backs. Horseshoe crabs can easily get flipped over on land by waves or other crabs, and they struggle to right themselves, leading to many aimlessly flailing their little legs in the air until the unfortunate crabs expire.

Related Topics: animals, conservation, fish and wildlife, horseshoe crab, nature, science