Outdoor Delaware is the award-winning online magazine of the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control. Articles and multimedia content are produced by the DNREC Office of Communications.

The term “invasive species” can conjure up a lot of images. For some, their minds jump to fish; for others, mammals; and for others still, it’s plants they think of. Regardless, it’s safe to say that for most people, the phrase “invasive species” doesn’t actually carry good connotations.

Areas all around the globe have been impacted by non-native species. Rabbits, introduced to Australia in the mid-19th century, quickly bred like, well, rabbits, and now outnumber humans several times over on the continent. Closer to home, the mid-Atlantic has seen invasions of northern snakeheads, garlic mustard and emerald ash borers, just to name a few.

These flora and fauna threaten to outcompete native species, might carry disease and generally risk disrupting the fragile ecosystem.

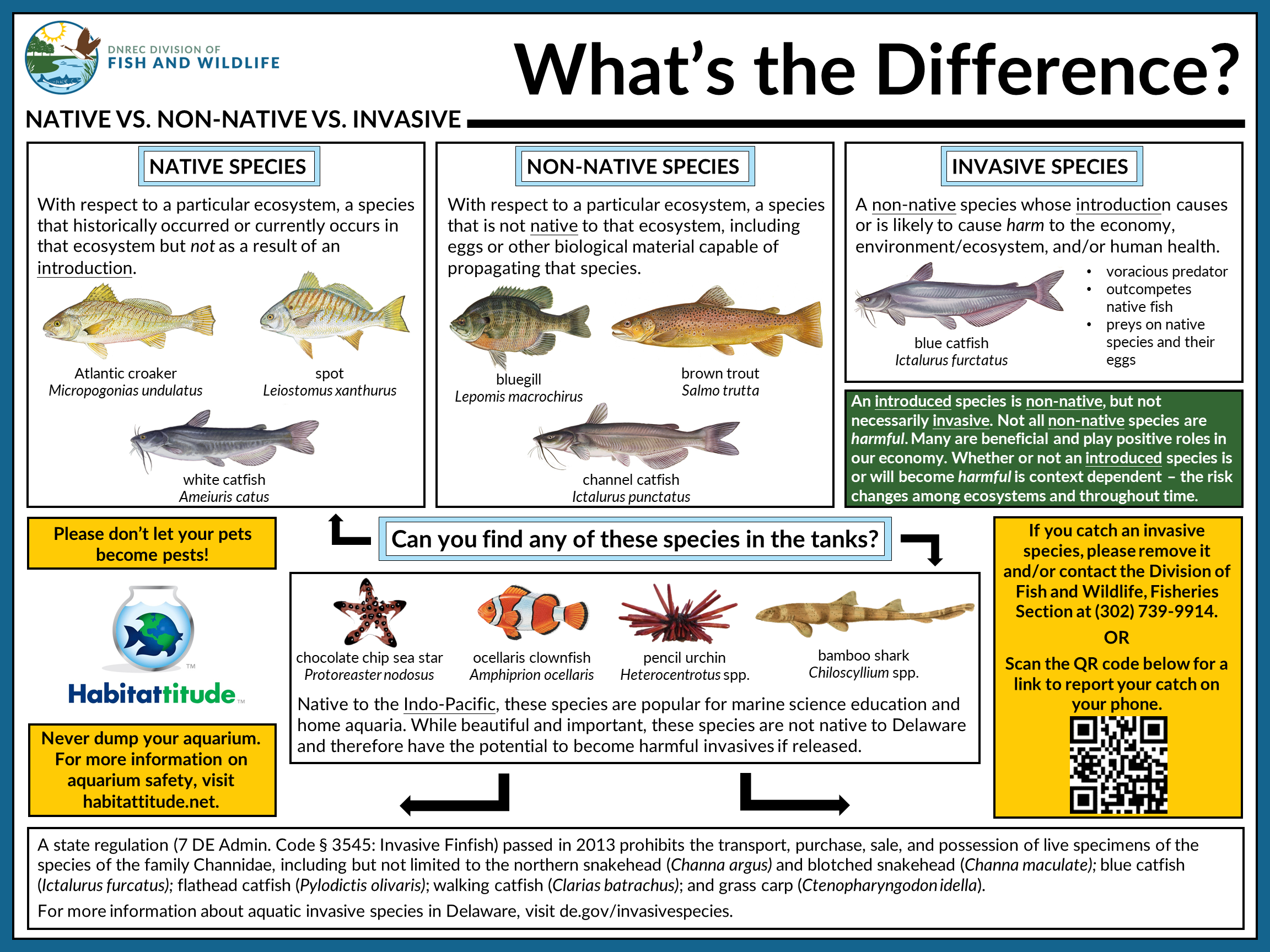

But what exactly is an invasive species? What differentiates an invader from a species that is simply native to one place and has come to settle in a different environment?

The U.S. Department of Agriculture defines an invasive species as one “whose introduction causes or is likely to cause economic or environmental harm or harm to human health,” noting food staples like tomatoes, lettuce and cows are all non-native to North America but are not considered invasive. In other words, all invasive species are non-native, but not all introduced species that come from elsewhere are invasive.

The term “invasive” can perhaps be a tad misleading — these plants and animals, after all, don’t set out as a marauding army to conquer and settle in new lands. There’s no non-human equivalent to conquistadors toppling mighty empires or Alexander the Great leading soldiers to victory over alien cultures half a continent away, though some invasive species have garnered significant public attention at times.

Rather, they can be taken to a new location deliberately, perhaps because they are visually appealing or simply remind an expatriate of home, or they can be transported accidentally, much as how rats have for centuries stowed away on ships and in the process settled all around the world.

The exact number of invasive species in Delaware is unknown, but according to state botanist Bill McAvoy, the state has 798 non-native plant species, of which 175 — about 11% of all flora here — are invasive.

“Non-native invasive species are so aggressive in their growth habits that they outcompete and displace native vegetation. They overtop, cast shade, and reduce available soil space for native species,” said McAvoy, who has been the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control’s foremost plant expert for 33 years. “In time, native plant populations slowly contract and decline to the point where they die out. You multiply that with overbrowsing by deer and native species really struggle to hold on. Deer don’t eat non-native species, simply because they don’t recognize them, or they have a disagreeable taste. There is a cascading effect when native plant species decline. Native pollinators and other invertebrates, as well as mammals, birds, reptiles, etc., that depend on these species for food and nesting, also decline.”

Benjamin Schlusser, the preserve steward at the Brandywine Conservancy and the chair of the nonprofit Delaware Invasive Species Council, said many invasive plants in Delaware arrived here within the past half-century or so. Often, they were deliberately introduced as ornamental species, only to spread and grow out of control, while others were planted in the mistaken belief they would be beneficial.

Some of the main invasive plants in Delaware include Japanese stilt grass, lesser celandine (also known as fig buttercup), multiflora rose, kudzu and autumn olive.

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Japanese stilt grass was likely brought here as packing material in shipments from China, while kudzu, autumn olive and multiflora rose were initially introduced as ornamental plants and for erosion control.

Invasive plants might harm native flora by hogging all the resources, such as in the case of kudzu. A vine native to East Asia, kudzu was introduced to the United States in 1876 during the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. Around World War II, the U.S. Department of Agriculture began leaning on it as a tool to prevent soil erosion and so encouraged its planting.

Unfortunately, as experts would eventually learn, kudzu can grow up to a foot per day and tends to cover everything in its way. For trees and other flora, this can prevent them from getting the necessary sunlight to survive.

Garlic mustard, introduced to North America from Europe in the 19th century, is another major threat among invasive flora.

Invasive plants may also carry insects that prove to be detrimental to native plants.

“We don’t just label something an invasive species just because,” Schlusser said. “Generally, if we’re calling it invasive, that means they’ve outcompeted them, so they’ve driven away and driven down our native biodiversity and left habitats with fewer plant species, and the plant species that are there are non-native.”

In 2021, the Delaware General Assembly passed legislation banning the transportation of about three dozen plant species designated by the state Agriculture Department as invasive. Most of these are originally from Asia.

That bill, Schlusser said, represents the largest step the state has ever taken to regulate nurseries and greenhouses.

For Delawareans, insects like the emerald ash borer and spotted lanternfly are prime examples of invaders.

Emerald ash borers inadvertently arrived in the country around the turn of the millennium in cargo imported from East Asia, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The insects’ larvae feed on the bark of ash trees, which leads to death within just a couple of years if left untreated. The species has devastated trees in the United States over the past few decades, as the trees here lack the resistance some Asian ashes possess.

Emerald ash borers were first detected in Delaware in 2016, making our state the 28th state with a confirmed presence. More members of the species were found in both New Castle and Sussex counties in 2018.

Though only around 2% of Delaware’s trees are ash, the presence of this shiny green beetle bodes ill for these towering trees. Delawareans are urged to avoid planting ash trees, while those who already have such trees on their property should consult a certified arborist for a health inspection. People who believe they have seen an emerald ash borer should contact the Delaware Department of Agriculture at 302-698-4500 and ask for the Plant Industries Section or the Delaware Forest Service.

Similarly, the spotted lanternfly was first detected in the United States in 2014 and in Delaware in 2017. This red and black bug from Asia poses a threat to a wide variety of plants, from apples to almonds to pine trees to rose bushes and more.

While some find this insect pretty, it’s a threat to the environment, and so Delawareans are urged to kill it on sight. When the bug first turned up in New Castle County, the Delaware Department of Agriculture imposed a quarantine, prohibiting individuals from moving plants, rocks, grills and many other objects or materials that could contain spotted lanternflies without first checking to be sure none of the invaders were present.

Delawareans who find a spotted lanternfly egg mass should use a stiff surface such as a credit card or putty knife to scrape the eggs into a sealed bag or other container and apply rubbing alcohol or an alcohol-based hand sanitizer to ensure the larvae don’t hatch.

The Delaware Department of Agriculture has since 2023 considered Vietnamese pot-bellied pigs, as well as feral swine of any kind, to be invasive, with the state witnessing a large increase in this species since 2016. The pigs “are not in good care; have been a nuisance for private property owners; and, with the species’ early reproductive capacity, can become feral quickly and may contract contagious and infectious diseases that can spread to both people and animals,” per the Department.

Residents are banned from taking in pot-bellied pigs and feral swine, although those who owned them before the regulation took effect were grandfathered in but still must obtain a permit from the state.

But of course, invasive species don’t have to live on land.

Delaware’s waterways are home to a number of unfriendly fish, as well as some aquatic plants. The “big three” in terms of invasive aquatic species here are, according to DNREC Division of Fish and Wildlife environmental scientist Michael Steiger, flathead catfish, blue catfish and northern snakeheads.

The northern snakehead was first caught in the United States in 2002 and confirmed in Delaware in 2010 in a tributary of the Nanticoke River. Native to Asia, this species is aggressive and feeds on many native fish, especially the young.

Like some other fish species, snakeheads may have been deliberately introduced so they could be caught by anglers. Unfortunately, they spread out of control, aided by their ability to “walk” on land from one body of water to another.

Flathead catfish were confirmed in Delaware in 2010, in this case in the Brandywine Creek, while blue catfish were first known to be living here in the Christina River in 2013.

Flathead catfish often prey on other fish species, making them a clear example of an invasive species. According to Steiger, flatheads weighing up to 40 pounds have been reported in the Brandywine River, and one stretching 38 inches and weighing 31 pounds was removed from Lums Pond in 2023.

The First State’s location in between the Chesapeake Bay and the Delaware River makes it a prime spot for invasive aquatic species, Steiger said, meaning an invasive species that turns up in a body of water in Maryland, Pennsylvania or New Jersey is very likely to end up in Delaware at some point.

Flooding can also transport aquatic species, both plants and animals, between waterways.

Steiger attempts to manage these and other invasive aquatic flora and fauna as best he can, as completely eradicating them is virtually impossible without also killing many other lifeforms. He has used electricity to shock flathead catfish in Lums Pond and then capture the stunned fish when they float to the surface.

“Every one I pull out isn’t reproducing and isn’t eating natives,” he said.

In fact, the DNREC Division of Fish and Wildlife has removed 91 flathead catfish from Lums Pond since July 2022. Unfortunately, many of these were sexually mature, indicating they were there for a few years and at least a few of them likely spawned young.

One of the ways the state tries to manage is by overstocking bodies of water with certain fish species. Analysis of the stomachs of flatheads has found yellow perch, white perch, bluegill and black crappie, so DNREC has stocked extra largemouth bass and bluegill in Lums Pond.

Anglers who spot an invasive fish can report it at https://survey123.arcgis.com/share/eaa188e68305437c910958147ebd135e, email DNRECFisheries@Delaware.gov or call 302-735-2966 or 302-739-9914.

In September 2024, a snakehead weighing almost 13 pounds — a new state record — was caught in the Appoquinimink River.

While there is no one agency responsible for managing invasive species, both DNREC and the Delaware Department of Agriculture play a role, with assistance from the Delaware Invasive Species Council. The council consists of representatives of government entities, academic institutions, landscaping and pest-control companies and others.

The council lacks regulatory authority, instead serving as an advisory body that tries to connect and spread knowledge. Formed in 2002, it aims to act as the go-to on invasive species in the First State and maintains a list of such species that the state can refer to. It uses criteria developed by the national nonprofit NatureServe as a guide for assessing invasive species.

The Delaware Invasive Species Council also provides grants, and in 2024 it awarded funding to Delaware Wild Lands, a conservation-based nonprofit. The council’s efforts are largely grassroots but have helped inform policies, such as the list of invasive plants compiled by the secretary of agriculture a few years ago.

Ultimately, one of the most important areas of the council’s work is outreach. Simply educating the public about the ways non-native species can harm the environment can help discourage individuals from purposefully spreading new plants and animals, and though we probably can never cut out accidental introduction, every bit helps. Among the resources on the council’s website are field guides and fact sheets about the flora and fauna of Delaware.

“People may not realize dumping something as simple as goldfish from your fishtank can have an impact. When dumped in the wild they compete with natives, and we’ve caught goldfish up to five pounds because they just eat and eat and eat in the wild, and that’s something people don’t realize,” Steiger said. “They dump their turtle, they dump their plants out of their aquarium or they keep them in their backyard pond and it floods. Just keep in mind that even something as small as dumping an aquarium with a few fish and few plants can have a lot greater effect than they think.”

Related Topics: animals, fish, fish and wildlife, insects, invasive species, native species, outdoor delaware, plants