Outdoor Delaware is the award-winning online magazine of the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control. Articles and multimedia content are produced by the DNREC Office of Communications.

For years prior to the late 1920s, the Indian River Inlet was a natural body of water, a small torrent that sliced between the shoreline to connect the Atlantic Ocean to the Inland Bays, though the exact location fluctuated due to storms and currents, shifting up and down the coast by as much as 2 miles.

Dredging — moving sediment from the bottom of bodies of water — began in 1928, with the first bridge built across the inlet in 1934 to connect Ocean Highway (now Del. Route 1), saving drivers significant time by no longer requiring them to take a lengthy detour around Millsboro. In the late 1930s, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers constructed stone jetties on each side of the inlet to provide stability.

All this change had many positive effects in terms of movement of people and goods, but it did pose a problem: disruption of the natural deposition of sand.

Sandy coasts along large bodies of water tend to see sediment primarily transported in one direction. This naturally moving sand helps prevent erosion by steadily replacing sections of beach lost to the waves.

At the Indian River Inlet, the natural flow of sand is south to north. However, because of the jetties, each of which stretches several hundred feet out into the ocean, that transfer of sediment — known as littoral drift — is interrupted.

As a result, the north beach has faced continuous erosion, especially given Delaware is the lowest-lying state and is thus particularly vulnerable to the impacts of sea level rise.

All that explains why the inlet’s sand bypass system was installed decades ago. The system was constructed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in the late 1980s and then turned over to the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control upon becoming operational in 1990.

DNREC has overseen the complicated machinery ever since, but in 2019, the aging system failed.

The outcome may have been influenced by the design of the Indian River Inlet Bridge. The newest iteration of the bridge, which opened in 2012, stands 45 feet above the water, 10 feet more than the one in place when the sand bypass system was built a few decades earlier.

That extra 10 feet is 10 more feet the sand and water sucked up by the system must travel against gravity, placing additional strain on the engines that adds up over the years.

Initially, DNREC predicted the system would be down about six months. But then something no one could anticipate flared up — a one-in-a-lifetime pandemic disrupted the global economy, causing supply chain issues that would take years to resolve.

Outdoor Delaware thought it would be useful to provide a primer on how the system works, including what beachgoers should expect and why the sand bypass won’t cure all ills pertaining to sea level rise, erosion and coastal storms.

Dozens of sand bypass systems have been developed around the world since the 1930s. A 1997 list of systems compiled by the Australian state of Queensland included 53 such systems, 36 of which were in the United States, with 16 of those in Florida.

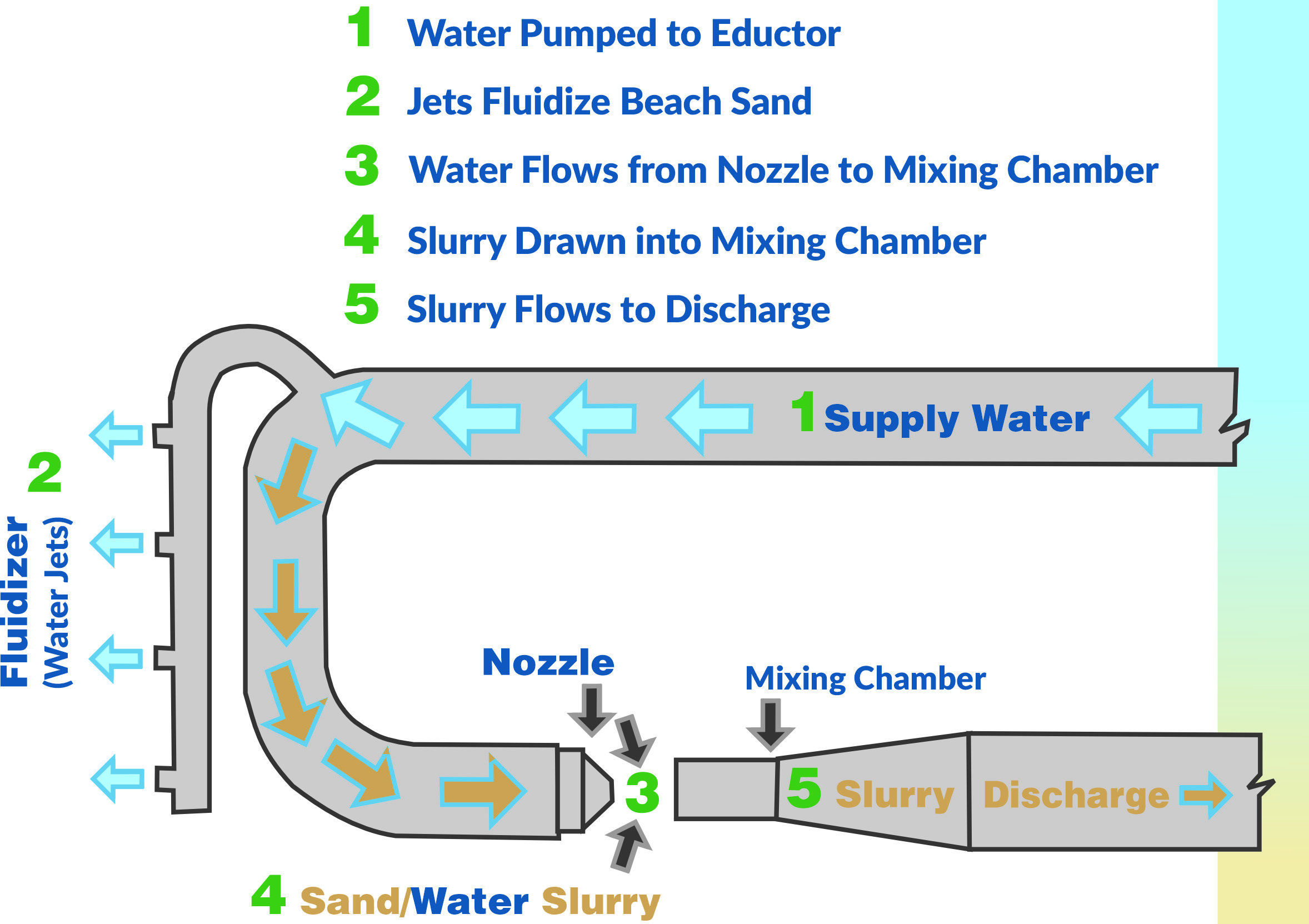

However, Delaware’s sand bypass system is the only one of its kind in the United States, according to Kathleen Bergin, a program manager in the DNREC Division of Watershed Stewardship who oversees the sand bypass system. While most systems have fixed equipment, the machinery at the Indian River Inlet is mobile. Specifically, the eductor head — a jet pump device that sucks up sand — can be moved using a crane.

“A mobile crane allows DNREC to access a broader range of sediment along the intertidal zone. Think of it like building a sandcastle: a fixed system is like standing in one spot and only being able to reach sand right around you,” Bergin said. “Our mobile setup is like being able to move around and collect sand from a much wider area — meaning we can build a bigger, more effective ‘sandcastle’ on the beach. This flexibility lets us maintain the beach more effectively by gathering material that might otherwise be out of reach.”

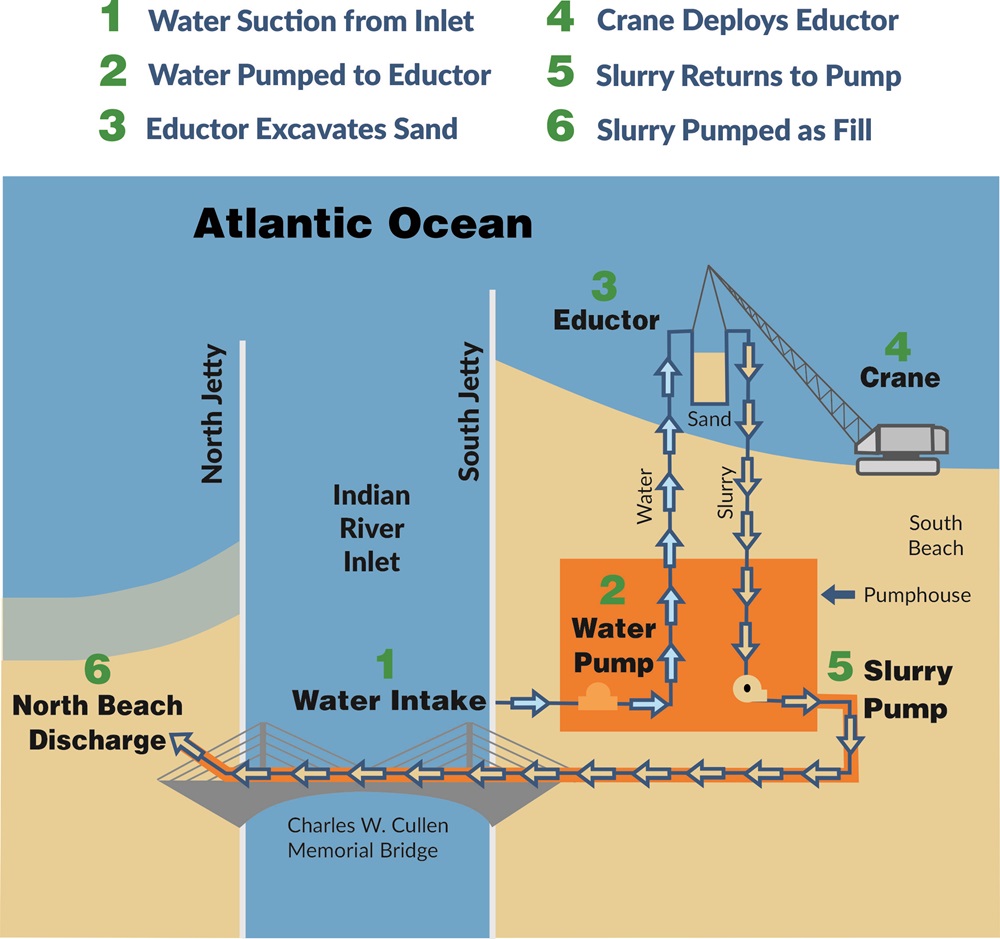

The system draws in water from the inlet and sends it through pipes to the pumphouse, a structure next to a public parking lot. From there, it’s routed through more pipes to the eductor, which is held above the beach by a large crane. Some water is forced out of fluidizer jets, wetting the surrounding sand, while the rest ends up in the eductor’s mixing chamber. A vacuum sucks sand and more water into the chamber, creating a slurry that is easier to transport and spread than just dry sediment.

This mix runs from the south beach, moving through pipes up and across the bridge before being deposited on the north side.

Trained DNREC personnel then move the sediment around the beach with heavy equipment like bulldozers, filling gaps caused by erosion and protecting Route 1 from waves. The sand deposited north of the inlet is used to cover a stretch of about 3,500 linear feet of beach.

The sand bypass was specifically designed for an area with minimal debris and sediment of relatively uniform size. It includes stone boxes that act like filters to catch larger debris before any rocks, driftwood or sizable shells can collide with the pump impellers.

The process as a whole is largely an attempt to mimic nature and replace the sand lost as a result of the manmade jetties reducing littoral transport.

“Because the sediment movement along the coast is a gradual perpetual process, a sand bypass system best replaces that natural process in that it’s continually feeding sand to the beach, as opposed to a periodic system where you’re dredging large quantities and slugs of sand that are less replicative of the natural process,” Randy Wise, a coastal engineer with the Army Corps of Engineers, said.

Absent the system, sediment will generally be carried miles offshore rather than making its way to the north beach, with some sand later returning farther north or being deposited in the ebb and flood shoals.

While the sand bypass system is an important part of DNREC’s strategy to manage climate change, it’s far from a panacea. The system is intended to help minimize the rate of erosion, not to permanently build up the beach.

The sand bypass can over the course of a year pump on average 100,000 cubic yards of sand — the equivalent of about 30 Olympic-sized swimming pools — though there’s variation from year to year depending on available sediment.

Unfortunately, the north beach is losing approximately 135,000 cubic yards annually due to manmade climate change and natural erosion.

“We’re still losing ground, but we’re holding the line as best as we can,” Bergin said.

Ultimately, Route 1 is a vital artery, with huge numbers of Delawareans and visitors taking the road down the coast every summer. Not only does the road make transporting goods and getting to and from beach communities easier, it has an important role as an evacuation route in the event of a disaster.

If the Indian River Inlet Bridge ever becomes inaccessible during a major weather event, traffic would be snarled up for miles in southeastern Sussex County as drivers are rerouted around the Inland Bays.

Contrary to what some residents may have assumed, the sand bypass system is not a replacement for a larger beachfill that draws from nearby shoals.

The Army Corps of Engineers conducted a large-scale beach nourishment project at the inlet in 2013 following Hurricane Sandy, and DNREC oversaw further beach nourishment in 2024 and earlier this year after the beach was eroded by storms and waves. Another phase, to be led by the Army Corps of Engineers, is scheduled to begin in the fall and should stabilize the beach before another significant renourishment effort is needed.

The bypass system itself requires specialized knowledge and must be overseen by trained workers at all times when running.

The public is urged to stay away from the inlet side of the south beach during active pumping periods, as the system can be dangerous. The eductor creates what looks like a large pit on the beach as it sucks up sand and produces a slurry on the south side to replenish the north beach, and anyone who stumbles in could be seriously injured by the machinery. The eductor can also cause strong rip currents, so beachgoers should be sure not to stray past the fencing around a section of the beach.

DNREC has signs on the beach indicating where work is taking place and instructing visitors to stay away for their own safety. Because the machinery is very loud and requires operators’ full attention, it is imperative individuals keep their distance to avoid risking injury.

Though the Department tries to run the system during off hours, such as at night, this isn’t always possible.

While there certainly has been a multiyear gap in operations involving the sand bypass system, the new engines have several clear benefits over the old ones. They are electric rather than diesel, meaning they generate less emissions and noise. Additionally, because they are more efficient, the engines will pay for themselves in about four years.

The engines cost about $300,000 collectively, although DNREC received a grant from the federal Diesel Emissions Reduction Act to offset about two-thirds of the cost.

The Department is also considering covering the pumphouse in solar panels or utilizing wind or hydrogen for energy, though more research is still needed to see if any of this is feasible, Bergin said.

As our state continues dealing with sea level rise, strategies such as dredging and using the sand bypass plant to manage erosion will only grow in importance, to say nothing of long-term steps like minimizing greenhouse gas emissions. Storms far offshore can still cause flooding here, which may lead to serious disruption to Delaware’s economy and residents’ daily lives if we do not prepare.

“Things that are happening 100 miles offshore severely impact our beaches,” Bergin said.