It’s a muggy and foggy Monday morning in August as Keri Maull and Andy Nitkowski board a boat at the Delaware Bay Launch Service in Milford. The boat shoves off and sails out onto the Delaware Bay, miles offshore past oil tankers like the Sonangol Cabinda.

Maull, a laboratory manager with the Environmental Laboratory Section within the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control’s Division of Water, and Nitkowski, an environmental control technician, will spend the next four hours collecting water samples from the bay using a variety of contraptions.

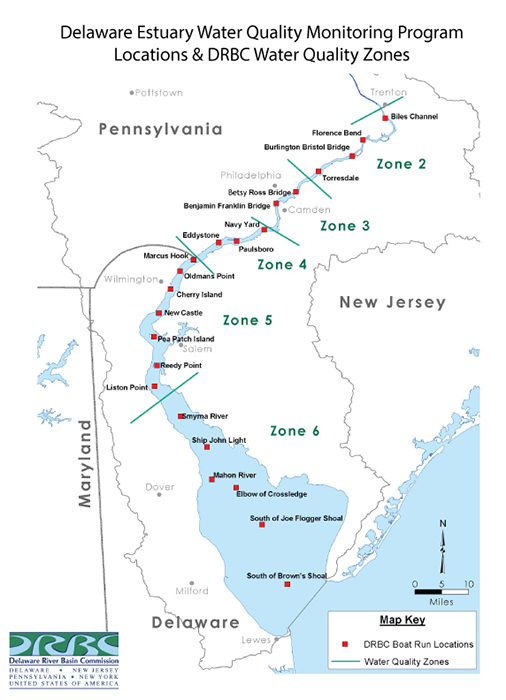

This exercise is the boat run, a monthly water-quality monitoring program. It is overseen by the Delaware River Basin Commission (DRBC), an interstate-federal compact consisting of Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York and the federal government. The DRBC contracts with DNREC to take water samples from the mouth of the Delaware Bay up to the head of tide in Trenton, New Jersey.

“We develop the scope of work, so we indicate where we want to monitor, what parameters, and we issue that contract to DNREC and they carry it out on our behalf. Then we scrutinize the data. The data informs a lot of our assessment activities so that’s the main function of it,” said John Yagecic, DRBC manager of water quality assessment.

Samples are collected at 22 different stations to check water quality, with a careful eye toward meeting certain criteria for things like dissolved oxygen, pH, temperature, and bacteria levels.

Launched in 1967, the Delaware Estuary Water Quality Monitoring Program, as it’s more formally known, is one of the longest-running water quality monitoring programs in the world, according to the DRBC.

“Because the Delaware River has drinking water intakes up and down the river from New York to Philadelphia and Camden, New Jersey, they need that water tested to ensure they’re not delivering polluted water to people who are drinking it,” explained David McQuaid, supervisor for the Division of Water’s Environmental Laboratory, with Maull noting that many people use the river and bay for recreational activities like fishing and boating too.

It’s been performed by DNREC for decades and takes place in various conditions. The water on this morning’s run, according to Maull and Nitkowski, is much calmer than the prior month’s iteration — a welcome change.

The DRBC sampling takes place every month from March to October. While two people — in this case Maull and Nitkowski — go out from Milford, two more leave from Smyrna and travel up to Trenton, stopping at various intervals to collect samples from the river.

Maull uses a series of hoses to pump water from the river into several small jars, while Nitkowski scoops some up in a bucket and transfers it to containers of his own. He also uses a secchidisk, a black and white disk on a rope that he dips into the river to measure water clarity. At each stop, Nitkowski carefully records his results on a data sheet before instructing the boat captain to head off to the next designated point for sample collection.

The locations they’ll be stopping at before heading back are south of Brown’s Shoal, south of Joe Flogger Shoal, the Elbow of Crossledge, Mahon River and Ship John Light.

While the locations have remained the same for years, the parameters do change from year to year on a rotating schedule.

Samples are analyzed by DNREC, but some samples are also sent to the New Jersey Department of Health, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and other cooperating partners.

“We don’t interpret results,” Maull noted — that’s reserved for the DRBC.

Because of the boat run’s longevity, there is a lot of data that can be reviewed, enabling the detection of trends.

“Having that long-term data is very useful to us now because we get to see over a long period of record how things have changed,” Yagecic said, pointing to dissolved oxygen levels as something that has seen dramatic improvement.

Dissolved oxygen is important because it is required for organisms like fish to thrive. Large algal blooms can lead to lower levels of dissolved oxygen, which can cause die-offs, especially toward the bottom of the water column.

The boat run helps determine whether the Delaware River will be listed as impaired in specific categories, such as if it has high concentrations of polychlorinated biphenyls.

“This is one of our critical ways of keeping eyes on the river,” Yagecic said. “This is our opportunity to measure the river and compare those measurements to criteria and see if we’re meeting criteria. So, it’s one of the fundamental tools that we use to know the condition of the river and whether that condition is good, bad or otherwise.”

Data can be viewed via the U.S. EPA’s Water Quality Data Portal. Bacteria data can also be viewed on the DRBC’s website, along with additional program information, at nj.gov/drbc/programs/quality/boat-run.html.

Related Topics: boat run, boating, nature, outdoor delaware, science, water, water quality