Outdoor Delaware is the award-winning online magazine of the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control. Articles and multimedia content are produced by the DNREC Office of Communications.

In recent years, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, better known as PFAS and sometimes referred to as “forever chemicals,” have entered the public consciousness as scientists have come to realize how prevalent these substances are in our water, soil, food and bodies.

The Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control has stepped up to the plate to help develop solutions to the problem, and in 2024, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency unveiled the first official limits for PFAS, as low as four parts per trillion for certain substances.

But how can policymakers even know if something is present in such a small amount? After all, four parts per trillion is literally 0.0000000004% — a total that can seem almost impossibly infinitesimal.

That’s where DNREC’s Environmental Laboratory comes in. Founded in 1949 as the Water Pollution Commission, it was intended “to maintain within its jurisdiction a reasonable quality of water consistent with public health and public enjoyment thereof, the propagation and protection of fish and wildlife, including birds, mammals and other terrestrial and aquatic life and the industrial development of the State.”

In 1966, the Water Pollution Commission was converted into a part of the Water and Air Resources Commission, which was itself reorganized into DNREC in 1969. Today, the Environmental Laboratory remains part of DNREC as a section within the Division of Water.

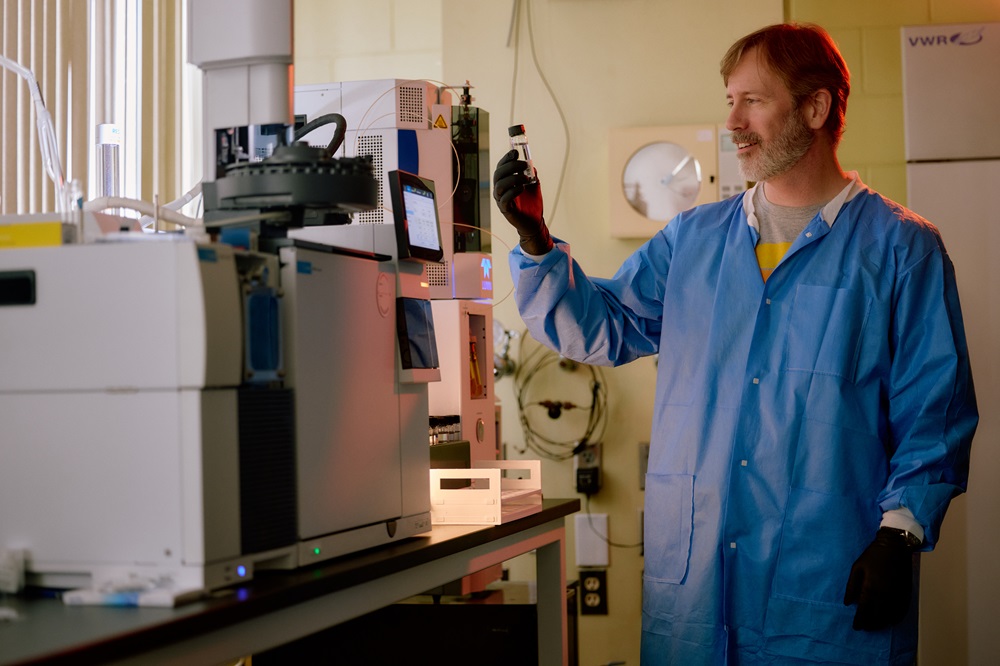

Throughout the decades, the laboratory’s core mission has remained unaltered even as its name and headquarters have changed. The team of about two dozen scientific, technical and support staff play a vital role in supporting DNREC by collecting and testing water samples for various contaminants, and their work helps inform the decisions of policymakers as they confront modern environmental and public health challenges.

“Our main role is to assist the surface water quality monitoring program that is run by the DNREC Division of Watershed Stewardship. We collect and analyze surface water and groundwater samples to better understand the health of the environment around us,” said environmental scientist Christopher Main.

Outside of DNREC, the Environmental Laboratory has roughly 50 clients, including U.S. EPA, the Delaware River Basin Commission and the U.S. Geological Survey. It also performs some tests for contractors working with DNREC.

The partnership with the Delaware River Basin Commission, an interstate-federal compact consisting of the federal government and the four states that border the Delaware River, is the longest continuous relationship the laboratory has, dating back around 60 years.

Laboratory staff look for various contaminants in samples collected, which can include nitrogen, phosphorus, heavy metals or bacteria. Their work helps detect potential pollution concerns for both humans and the environment and is of course vital as Delaware continues to respond to the growing issue related to PFAS and other emerging contaminants. Currently, Main is working on environmental DNA, which is DNA that can be found in the natural environment from skin cells, feces and other environmental sources and can be used for the detection of rare and invasive species.

Although it does not oversee bodies of water per se, the laboratory is responsible for testing the Nanticoke River near Seaford, Brandywine Creek by Wilmington and many other bodies of water in between. Its personnel are generally dispatched several days a week to collect specimens, with the laboratory taking in roughly 200 to 300 samples a month. Some come from DNREC staff, while others are submitted by outside entities or individuals and then analyzed by the laboratory.

Throughout it all, the laboratory’s staff keep a core aspect of their duties in mind: They produce data from the samples that have been tested but leave the interpretation up to the clients.

“As a laboratory, we’re a neutral, unbiased entity,” Director Ashley Kunder said. “We assess the data for analytical quality, not necessarily how it relates to the environment from an ecological viewpoint.”

Unlike many DNREC programs and services, the laboratory lacks regulatory authority.

Contrary to the common popular image of a laboratory, DNREC’s Environmental Laboratory is not just made up of chemists and microbiologists but also includes other vital employees such as technical and support personnel who help keep things running.

“We also can’t forget that we wouldn’t be a laboratory without technical and support staff,” Kunder said.

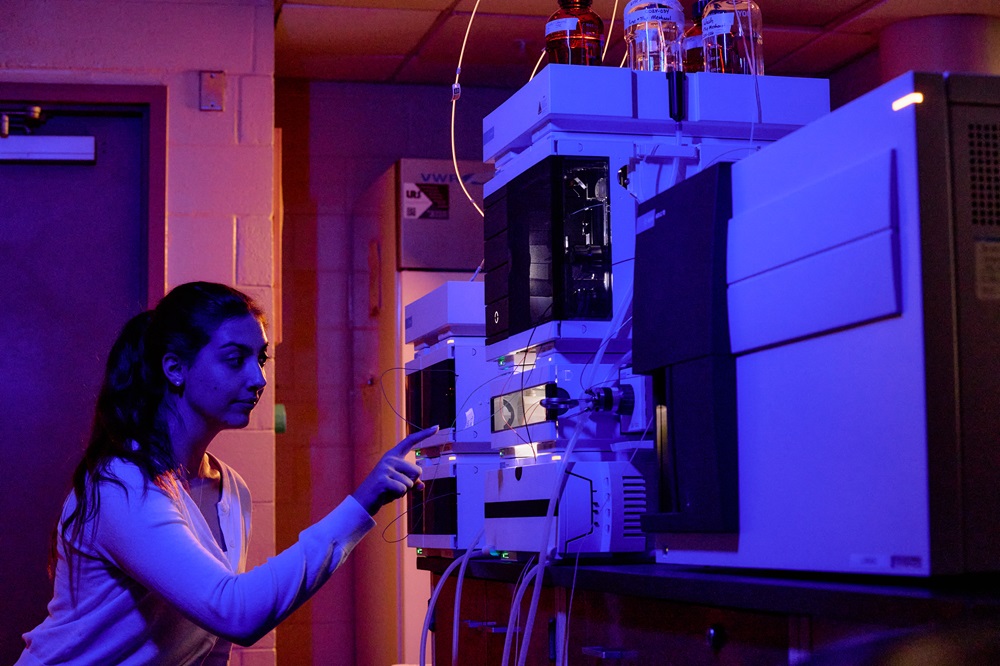

The laboratory’s employees use a variety of sophisticated, specialized equipment, such as a liquid chromatograph with tandem mass spectrometry, which analyzes substances for various compounds. These machines, which can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, are vital for the laboratory to be able to detect chemicals like PFAS at scales of parts per billion or even trillion.

The laboratory is also expanding into other types of sample testing, such as tissue, soil and air.

It is currently working on expanding its testing capability to include microplastics, as well as emerging contaminants like 6PPD-quinone, and laboratory personnel are constantly looking for new and improved methods of conducting tests.

Despite the important work the laboratory performs, its personnel face some challenges, particularly a workspace that is in many ways unsuited for their duties. Downtown Dover’s Richardson and Robbins Building, where the laboratory and many other DNREC programs and services are based, was originally built in the 1800s as a cannery. The building eventually was purchased by the State and a portion was repurposed into laboratory space in the 1980s.

Much to the delight of current employees, a new laboratory is being constructed on the grounds of the Delaware Department of Health and Social Services campus in Smyrna. This state-of-the-art facility, which is expected to be complete in spring 2026, is specifically designed to support safer and more efficient analysis.

“Part of the construction of the current laboratory building causes problems for what we do based upon what the materials were made out of,” said Dave McQuaide, the laboratory’s field supervisor. “We have come so far since my start here 33 years ago, but with increasingly lower target analysis numbers, our equipment has certainly improved quite a bit but the environment around it remains the same. All the systems are designed for an actual laboratory instead of a chicken canning operation.”

Being so close to the Division of Public Health’s laboratory will also be beneficial, making it easier for experts to share knowledge and supplies when needed.

“This new state-of-the-art laboratory will support DNREC’s mission to protect Delaware’s natural resources, public health and the environment,” Kunder said.

Related Topics: environmental laboratory, groundwater, health and science, laboratory, outdoor delaware, PFAS, science, surface water, testing, water testing