By Jeff Tinsman

It took about two-and-a-half hours for her to go under. She went down bow first in 88 feet of water. But the 180-foot-long ship, The Reedville, wasn’t caught in a storm. She was purposely and carefully sunk in the summer of 2020, just another addition to the renowned Delaware Artificial Reef Program.

The Reedville joins a multitude of New York City subway cars on the bottom of the ocean at Redbird Reef about 16 miles off the Indian River Inlet. The reef, which covers 1.3 square miles of the ocean floor, is specifically designed to provide fish habitat, opportunities for angling, SCUBA diving and other activities for ocean dwellers and sea lovers alike.

Delaware’s 14 reef sites are located along the coast from Augustine Beach to 55 miles offshore along the edge of the continental shelf. Most are still numbered, but three sites have been named, including Redbird Reef, which contains more than 700 retired and repurposed “Redbird” subway cars from New York.

Over the past 20 years, the Delaware Artificial Reef Program has used recycled materials for reef development. These materials include more than two million tons of rock, 100,000 tons of concrete, 86 tanks and armored personnel carriers, upwards of 1,350 retired subway cars and 29 retired vessels ranging from 40 to 653 feet long.

The latest sinking came in July 2024, when a retired Baltimore fireboat and a World War II-era tugboat were sunk onto the Redbird Reef. The two now reside in roughly 75 feet of water.

“Our giving these boats a continued existence as reef deployments cultivating marine life while providing recreational fishing and diving opportunities also pays tribute to what they once were, when they served our country’s maritime and public safety needs,” DNREC Secretary Shawn M. Garvin said. “And every trip out to Reef Site 11 for anglers and divers can bring reflections harking back to their service when afloat.”

The July 2024 sinkings were carried out by contractor Coleen Marine, which has handled numerous reef deployments over the DNREC reef program’s existence. As with all other vessels DNREC has deployed onto the artificial reef system, the most recent ones were sunk only after having been certified for environmental cleanliness and safety.

Artificial reef development first came about in 1985, under the direction of the National Artificial Reef Plan, written by the National Marine Fisheries Service, part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). We dedicated a federal aid project to artificial reef development in 1992 and began deploying reef materials in 1995. Funding for the artificial reef program comes from federal taxes on fishing and boating equipment. No state funding is used.

Artificial reefs mimic the functions of coral reefs. They provide durable, stable manmade structures on specially permitted sites. They are located so they will attract fish but not interfere with navigation or other uses.

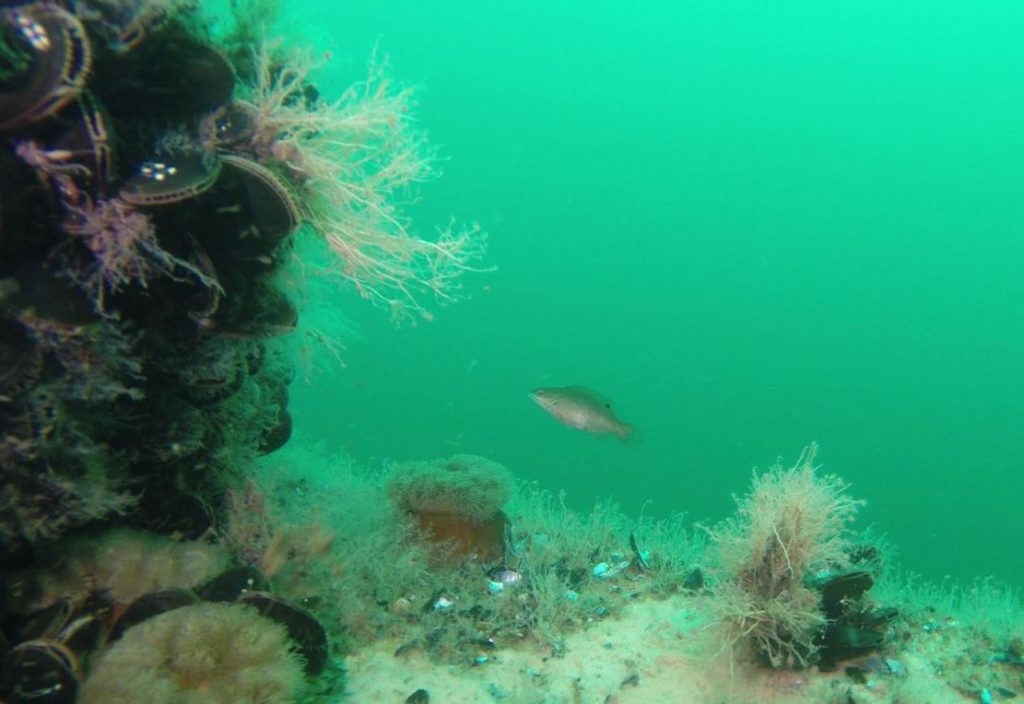

A rich and unique invertebrate community, including blue mussels and oysters, attach to the surfaces of our artificial reefs. These creatures provide up to 400 times more food for fish as the bare ocean floor. The three-dimensional reefs also provide protection for fish from predators, tides and storms.

Once the fish arrive, so do anglers. But overfishing is avoided by placing size limits for tautog, black sea bass and summer flounder, the fish usually caught on Delaware’s reefs.

Artificial reefs are considered most important in the mid-Atlantic region because we have limited natural rock, unlike New England or south Florida with its tropical coral reefs. In Delaware, artificial reefs alone provide this kind of enriched habitat.

Our artificial reef system grows bigger every year. Vessels are bought and prepared for reefing by a marine contractor with a shipyard near Delaware. Due to the high cost of towing, all reefing candidates must originate locally. Marine contractors perform many types of jobs including towing, and salvage and marine repair. We use a marine contractor specializing in reef development.

The reef program is conducted under a federal permit from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers with oversight by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency for toxics removal, and the U.S. Coast Guard for elimination of petroleum and floatables. As a result, the reef program is environmentally sound.

For a small coastal state, Delaware has an active and well-funded reef program. The fish and anglers are benefitting, and so is our economy. Our monitoring of angler use shows that fishing on our reefs results in a $7 million annual boost to the coastal economy. This benefit is based on angler spending for food, lodging, bait, tackle and boating. In 2021, Delaware’s artificial reefs received more than 63,000 boat trips from anglers.

It’s been my pleasure to have run the Artificial Reef Program since its inception. As my retirement approaches, I’m pleased to see its popularity grow into more than I imagined it would.

It’s been my pleasure to have run the Artificial Reef Program since its inception. As my retirement approaches, I’m pleased to see its popularity grow into more than I imagined it would.

My favorite part of the program has been SCUBA diving the sites on a rare clear-water day. I’ve seen the food chain first-hand, from blue mussels and swarms of black sea bass, to predators like bluefish schooling above the wrecks.

Reef building will continue. Plenty of undeveloped space remains on our permitted sites and I look forward to seeing the results of the next generation of reef builders.

Related Topics: boating, conservation, education, fisheries, fishing, Fishing and Hunting, fun, health, nature, outdoor delaware, outdoor recreation, recycling, reefs, science